Three Important Things

1. pix2pix-zero

The authors tackle the problem of ensuring faithfulness to the original source image in image-to-image translation driven by diffusion models. The difficulty of image-to-image translation is that while we specify the edits that we want (i.e changing a dog in the scene to a cat), we do not specify what we want to preserve, which is implicit.

They come up with a technique that they call pix2pix-zero, which is training-free and prompt-free. Training-free means that it does not require any fine-tuning on existing diffusion models, and prompt-free means that the user does not have to specify a prompt, but simply only the desired changes from the source domain to the target domain, i.e cat -> dog.

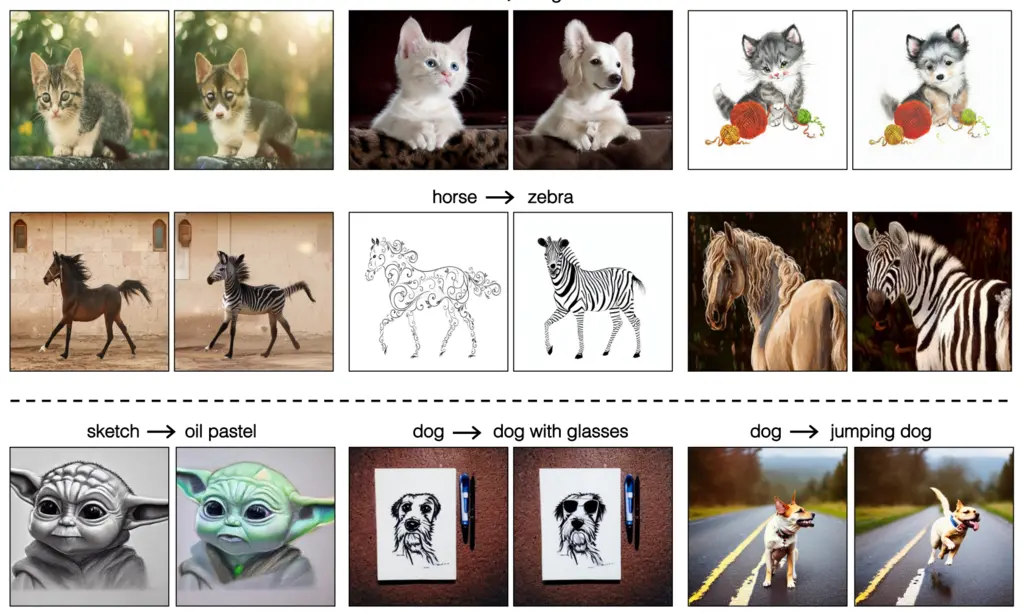

Samples of their results:

Their approach consists of two main contributions:

- An efficient, automatic editing direction discovery mechanism without input text prompting,

- Content preservation via cross-attention guidance.

The two techniques are discussed in the following sections.

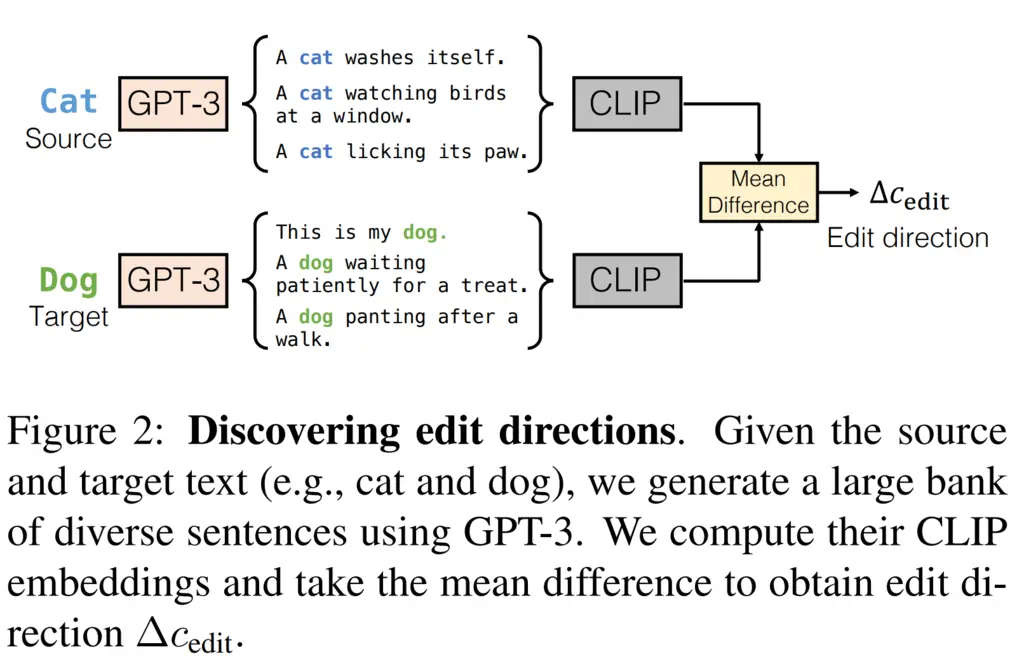

2. Discovering Edit Directions

Given just a textual description of the edit (i.e cat -> dog), the first problem is how we can translate this to a direction in embedding space.

To do this, they used GPT-3 to generate two groups of a large number of diverse sentences: one containing the source text, and one containing the target text. They then took the average CLIP embeddings of each group, and took their difference as the edit direction to use. They denote this final edit direction \(\Delta c_{\mathrm{edit}}\). They found that this approach of taking the mean CLIP embedding of many sentences containing the word instead of just the embedding of the word itself to be more robust.

The following diagram summarizes the process:

Computing the edit directions takes about 5 seconds, and only needs to be performed once for each source-target edit pair.

3. Editing via Cross-Attention Guidance

They base their image generation model off Stable Diffusion, which is a latent diffusion model. The Stable Diffusion generation process allows conditioning on an input text, which is converted into a text embedding \(c\). This conditioning is performed by the attention mechanism:

\[\operatorname{Attention}(Q, K, V)=M \cdot V,\]where \(M=\operatorname{Softmax}\left(\frac{Q K^T}{\sqrt{d}}\right)\) with:

- \(\varphi(x_t)\) being the intermediate features from the denoising UNet,

- \(c\) being the text embedding obtained via BLIP from the input image,

- \(W_Q, W_K, W_V\) being learnt projections,

- Query \(Q = W_Q \varphi(x_t)\) being applied on the spatial features,

- Key \(K = W_K c\) and value \(V = W_V c\) being applied on the text embeddings.

Intuitively, \(M_{i,j}\) is the importance of the \(j\)th text token to the \(i\)th spatial location. Note that \(M\) actually depends on the time step \(t\) due to its dependence on \(x_t\), so we have different attention maps for each time step.

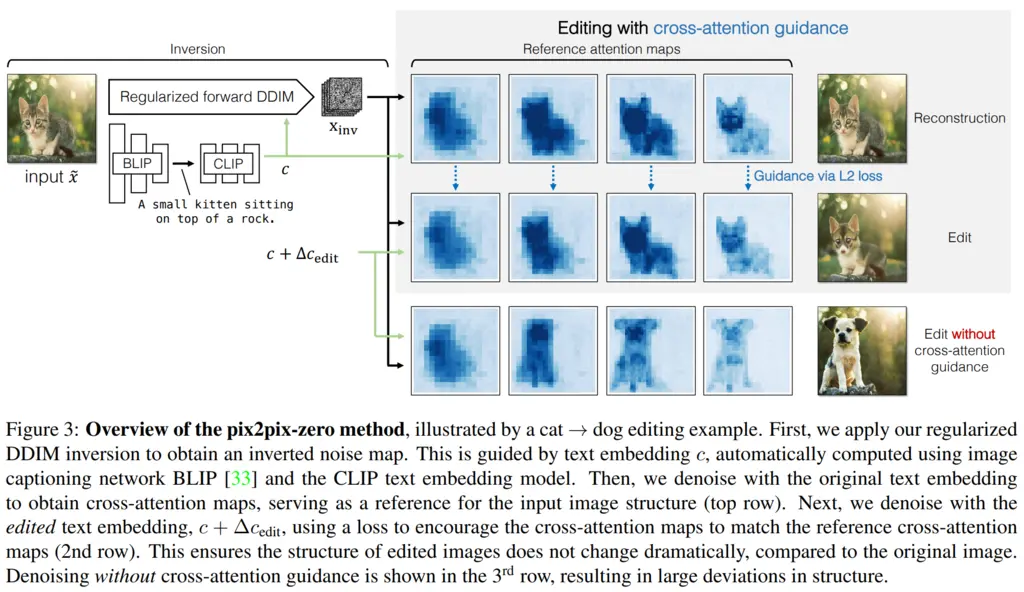

To obtain the text embedding in the absence of any textual inputs other than the source and target, they used BLIP on the source image to obtain a caption, and then applied CLIP on that caption to obtain the embedding.

A naive approach might be then to simply condition on the sum of the text embedding and the edit direction \(c + \Delta c_{\mathrm{edit}}\), but as the following figure shows in the last row, this results in a final generated image that is quite different from the original source image:

Instead, their key insight is that the cross-attention map generated from the embeddings \(c + \Delta c_{\mathrm{edit}}\), denoted \(M_t^{\mathrm{edit}}\), must be regularized towards the original cross-attention map from the original embedding \(c\), denoted \(M_t^{\mathrm{ref}}\).

By encouraging the cross-attention maps to be close, there is better control over the denoising process to ensure that the final image stays faithful to the source.

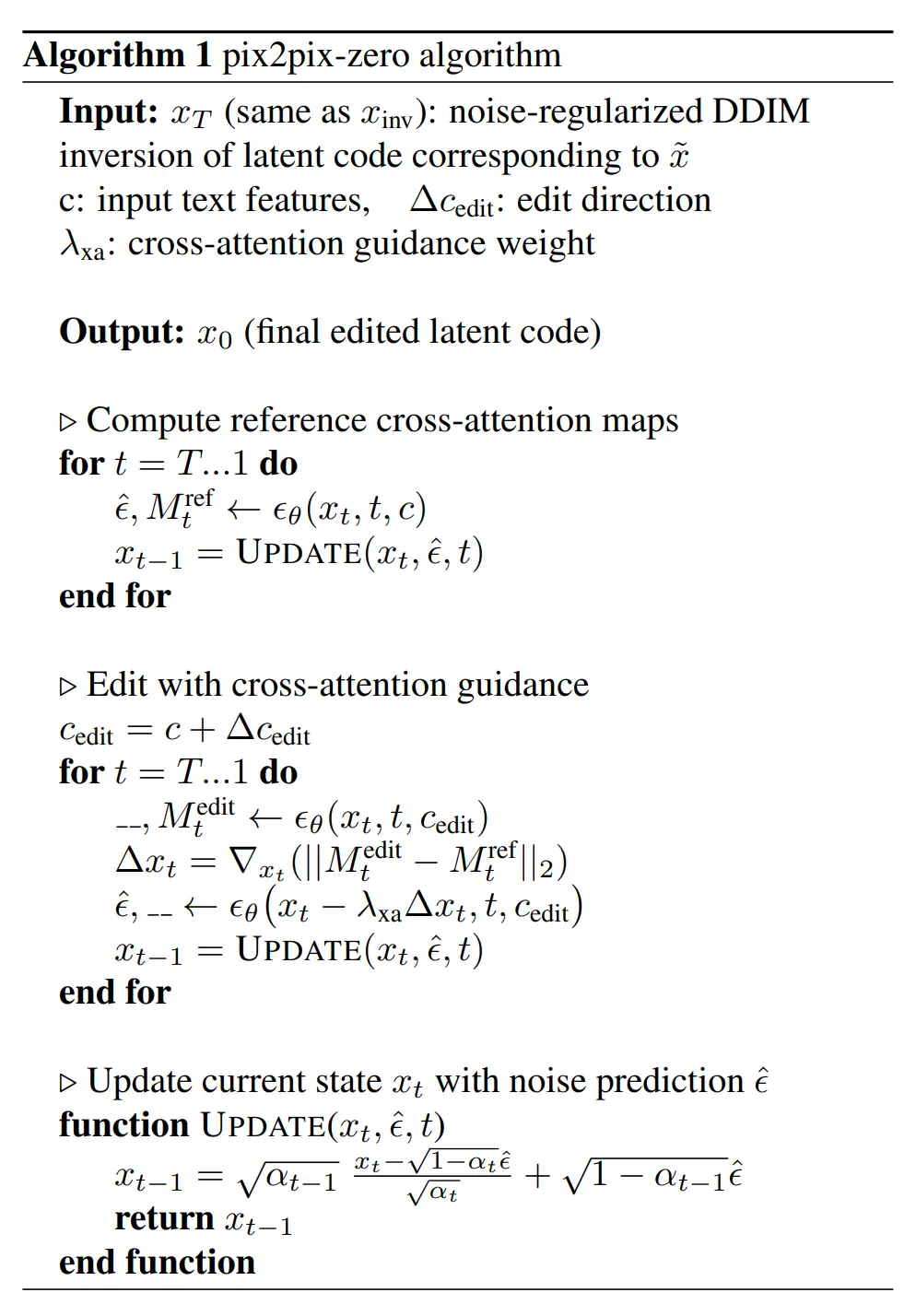

Their algorithm works as follows:

- Run the reverse diffusion process starting from noise conditioned on the original text embedding \(c\), and store the reference cross-attention maps \(M_t^{\mathrm{ref}}\) at each time step

-

Now run the reverse diffusion process conditioned on \(c + \Delta c_{\mathrm{edit}}\), but after getting the original attention mask \(M_t^{\mathrm{edit}}\), we want to work towards reducing the cross-attention loss \(\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{xa}}\):

\[\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{xa}}=\left\|M_t^{\mathrm{edit}}-M_t^{\mathrm{ref}}\right\|_2\]This is achieved by applying a single gradient step scaled by some step size \(\lambda_{\mathrm{xa}}\) onto the current latent \(x_t\) so we now have a new latent that would result in slightly better cross-attention loss

\[x_t\prime = x_t - \lambda_{\mathrm{xa}}\Delta x_t=\nabla_{x_t}\left(\left\|M_t^{\text {edit }}-M_t^{\text {ref }}\right\|_2\right),\]and then using that to obtain the new noise prediction \(\epsilon_\theta\left(x_t\prime, t, c_{\text {edit }}\right)\), which is used to update the latent.

The full algorithm is given below:

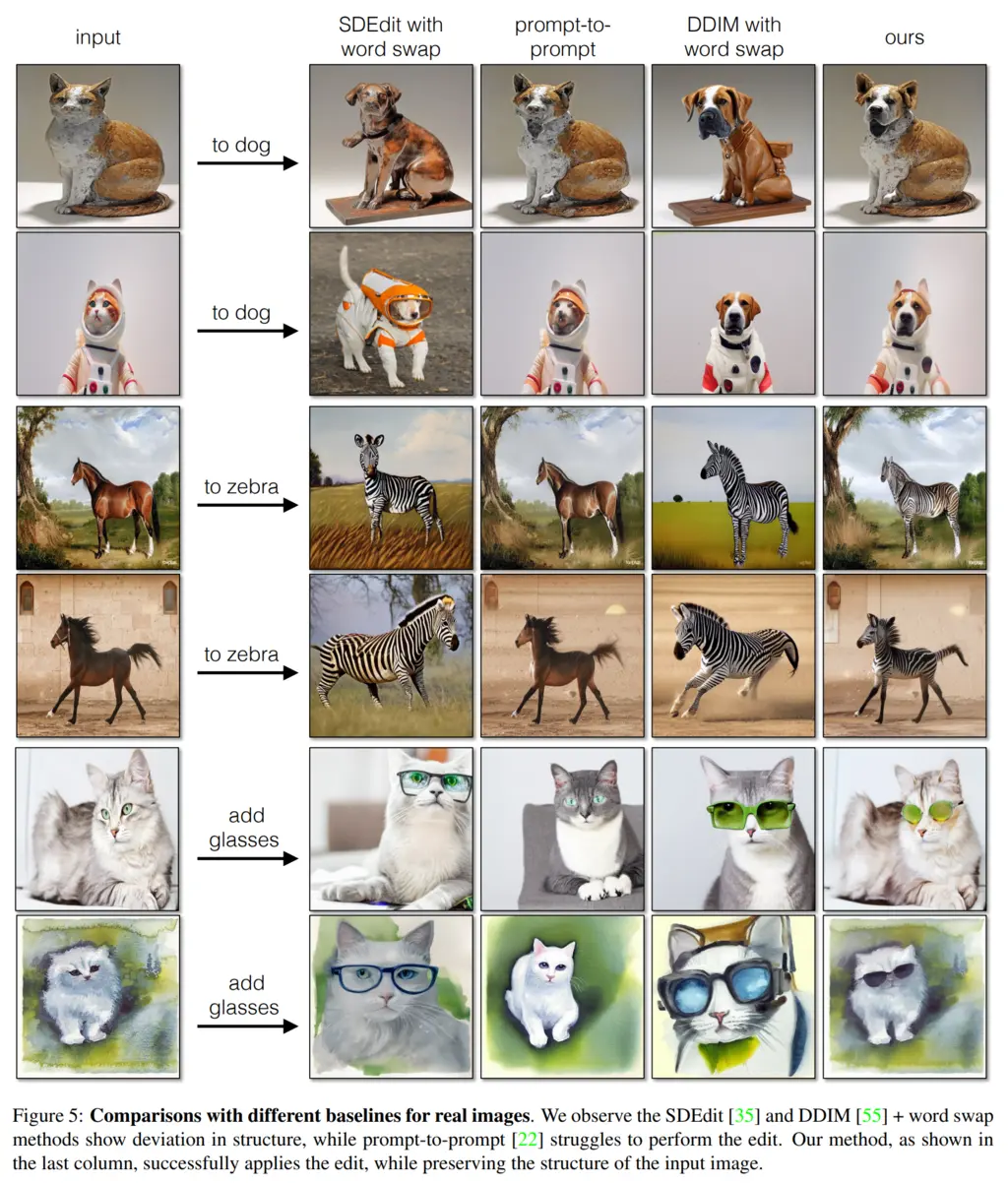

Finally, some nice visual comparisons of their results with other state-of-the-art techniques:

Most Glaring Deficiency

It is possible for the reference diffusion process to already diverge in some ways from the original source image, since the latent cannot capture all information about the source image. Therefore, our final target image actually has two sources of divergences from the source image: from the divergence of the denoising process of the reference image embedding, and also from the divergence due to the difference in the text conditioning.

The latter seems unavoidable, but we might hope to find ways to improve on the former, perhaps by penalizing reconstruction loss in some way as well.

The paper also mentions limitations of the cross-attention maps, which is \(64 \times 64\) in Stable Diffusion, but this seems like less of a fundamental limitation than what I mentioned above.

Conclusions for Future Work

The insight in this paper of ensuring that image to image translation is consistent is to apply a form of regularization between the attention maps to encourage the diffusion process between the source and target to be more similar. This idea of tying together various parts of a generative process when we want similar outputs could also be applied to other techniques and problem domains.